Joan Witek in her Duane Street Loft, NYC, 1974. © Joan Witek Studio & Bartha_contemporary

The New‑York artist Joan Witek (b. 1943) has been exploring the depths of a single colour for almost half a century. From her early figurative work in the late 1960s, she moved towards geometric abstraction, and by 1974, Witek focused her palette to black. The artist did not choose black because it denotes a modernist approach, but because it offered infinite variety. She remarked that black is sophisticated and primitive, emotional and intellectual, but most and foremost, it is a colour that everyone responds to. This exploration of black has made her a distinctive voice in American abstraction, situating her work within broader discourses around colour, process, and materiality.

Witek's engagement with black comes out of a long artistic lineage. Frank Stella's Black Paintings (1958–60), Ad Reinhardt's black monochromes and Richard Serra's paint‑stick drawings demonstrated that black could be a complete universe rather than a neutral void. Art historian Lilly Wei has placed Witek within this canon, noting that she plays on black's oppositions: ascetic yet alluring, meditative yet expressive, fierce yet demure. Recent writing on the colour's history emphasises how artists such as Stella and Reinhardt showed that black paintings contain multiple tonalities. Indeed, no two blacks are the same. Witek extends this idea by continuously reinventing how black behaves when it is the only hue.

Witek studied with Pearl Fine and Halston Crawford at Hofstra University and Morris Kantor and Knox Martin at the Art Students League and worked as an assistant curator in the African, Oceanic, and the Americas department at both the Brooklyn Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Around 1966, Witek produced a series of eight figurative woodcuts inspired by The Hamptons Album, and then abruptly began creating geometric canvases, primarily influenced by her studies of the art of New Guinea. Witek got her break into the New York art scene when she was awarded the Lowe Foundation Grant, with Louise Nevelson as the juror. A turning point ensued in 1974 when she created a large, four-part painting using oil stick and graphite on unstretched canvas. On the occasion of her major survey at the Carnegie Museum in 1984, curator John Caldwell compared her work to that of Richard Serra, observing that Witek built forms through rows of parallel lines rather than outlining shapes, thereby giving her compositions a brooding presence. She mixed oil pigment with powdered graphite to create surfaces ranging from silvery sheen to velvety black. By condensing her palette to a single colour, Witek sought to accentuate scale, surface and gesture.

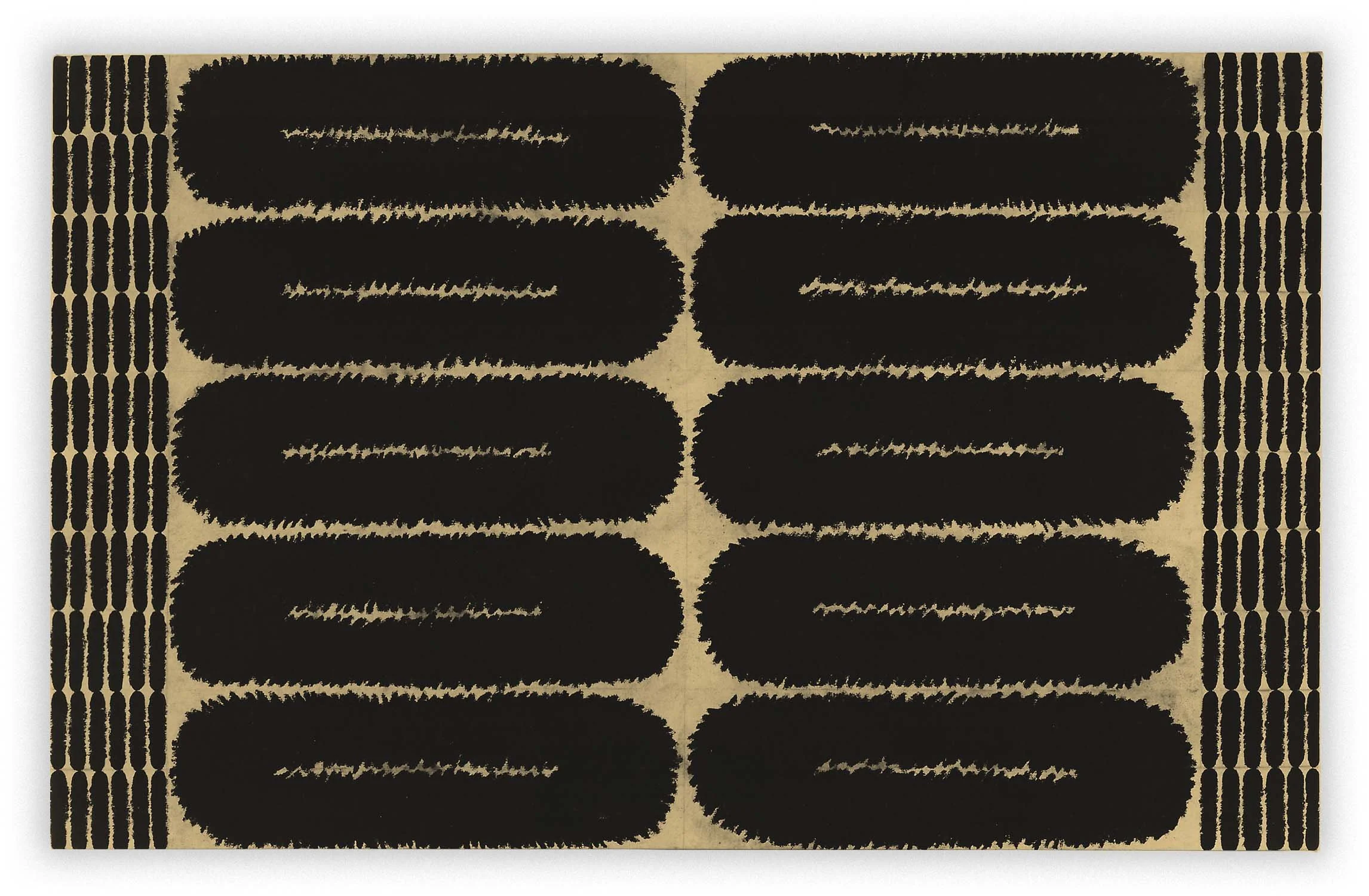

In 1978, Witek began creating pencil and ink drawings composed of thousands of repeated strokes, which the artist arranged in a grid-like pattern. These works became her "grammar" of mark-making, establishing a personal script that she refers to as her handwriting. The grid provided a rational structure, while the hand-drawn marks introduced a distinctive irregularity; this tension between order and intuition persists throughout her work. A 1988 review in Art in America observed that Witek's surfaces, whether "flecked, splattered, smeared, dripped or stroked", are always authoritative because of the tension between unadorned compositions and complex execution. Despite their austerity, the drawings radiate a spiritual aura reminiscent of Agnes Martin.

During the late 70s and early 80s, Witek developed her "stroke" paintings. Using oil stick on canvas, she built fields of lozenge‑like forms that appear to tremble against one another. Critics noted that the viewer must look closely to discern subtle variations; as Witek said during a 2014 exhibition, "Sameness makes you look harder". Her titles often quote literature or poetry, adding a linguistic layer to what might otherwise be non-objective works. By the early 2000s, she began working on white gessoed grounds, overlaying them with ink or graphite to create shimmering, almost calligraphic surfaces she refers to as "black impressionism".

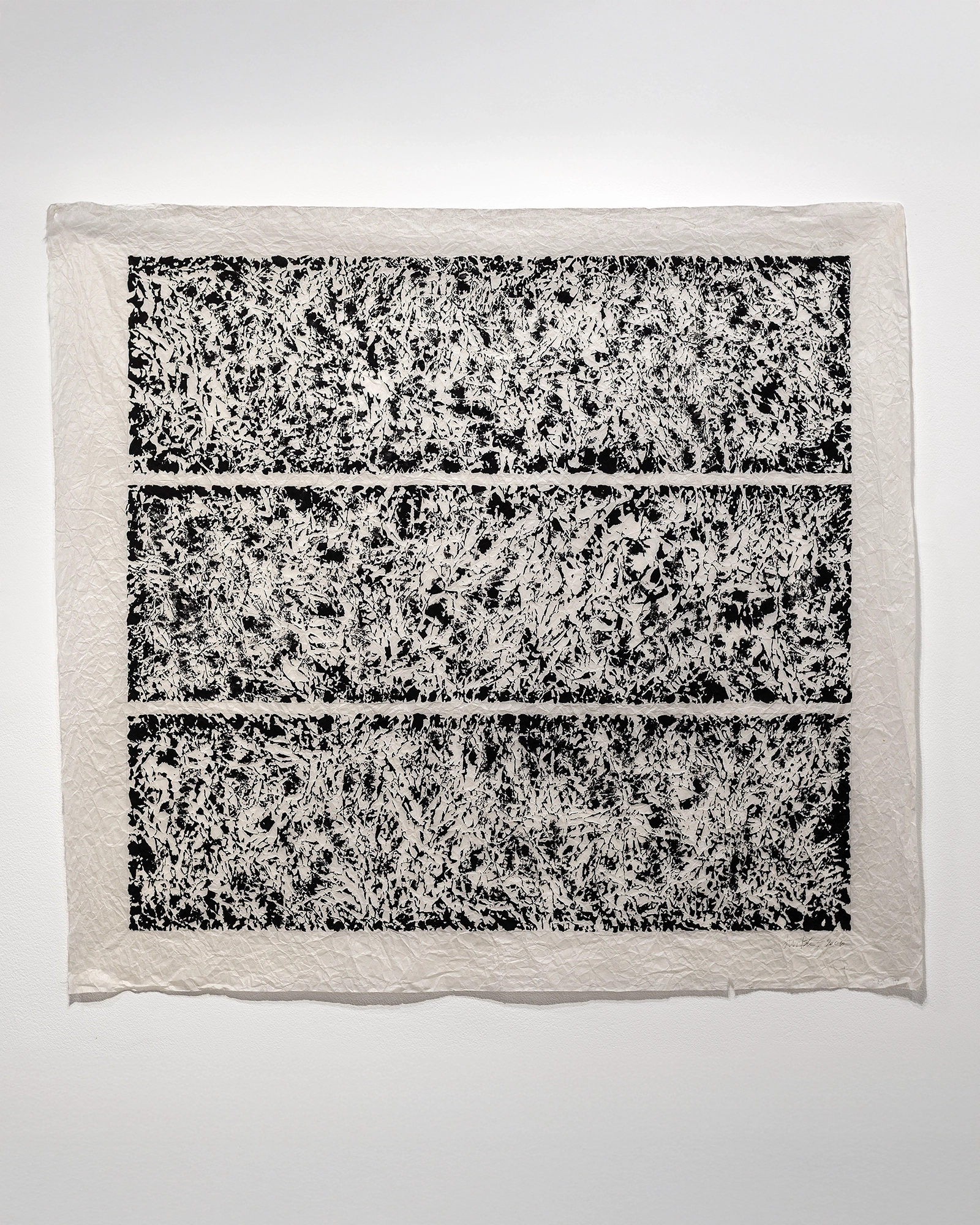

Rice paper has been central to Witek's drawing practice since the mid‑2000s. She values the material for its translucency and fragility; washes of ink or watercolour sink into the fibres, creating atmospheric veils. Witek's Mirabai series, begun after 2000, transcribes poems by the 16th-century Indian poet Mirabai into repetitive pen strokes on rice paper, transforming devotional texts into abstract grids. The tactile quality of the material is integral to the work: viewers "can almost feel the creased rice paper" and sense the buoyancy of the ink. Each sheet is a meditation on time and labour, merging Eastern calligraphic traditions with modernist minimalism.

Indeed, these "expressions of a black watercolour on delicate, wrinkled rice paper" expanded two-dimensional works into the realm of reliefs. The limited palette heightens the sensorial qualities of the support: the paper buckles, absorbs and reflects the pigment, creating subtly shifting blacks that recall ink‑wash landscapes.

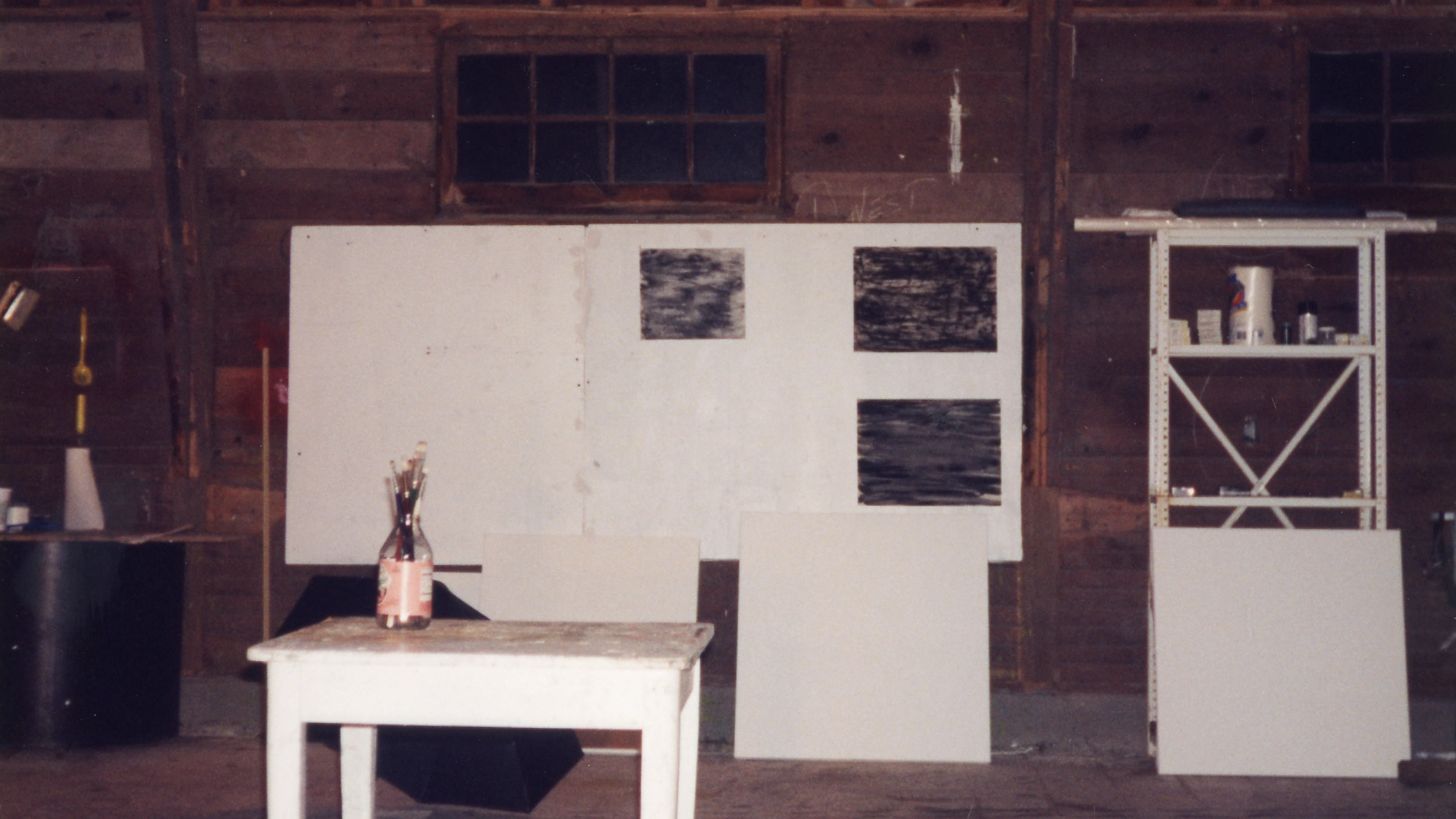

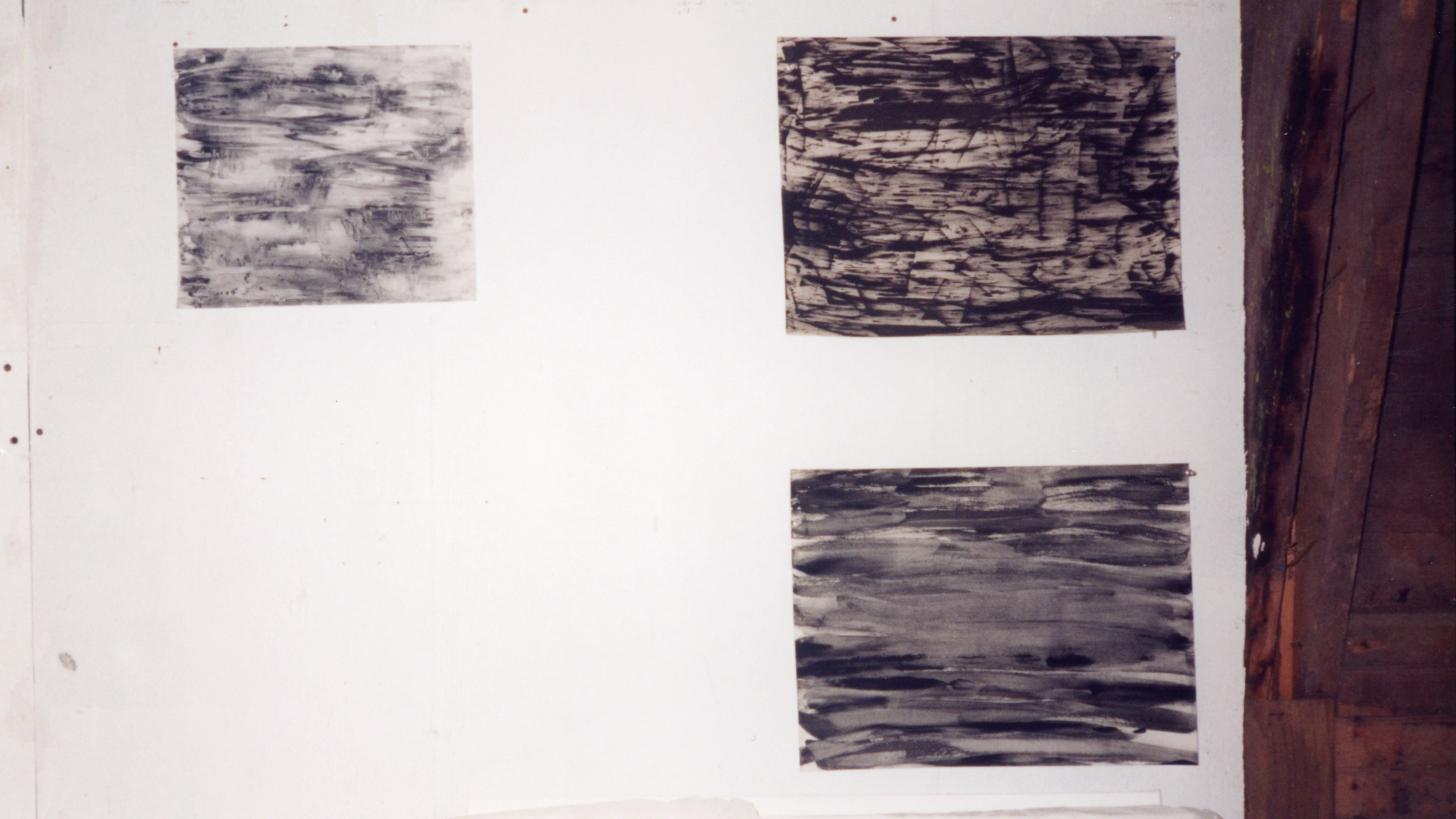

In 1995, Witek spent a residency at the Edward Albee Foundation's barn in Montauk, Long Island. During this period, she produced a suite of watercolours on film and paper. These works differ from her dense stroke paintings; they explore light, horizon and atmosphere, perhaps inspired by the coastal environment. Unlike the saturated blacks of her oil paintings, the Montauk watercolours allow washes to dry into ghostly layers, revealing Witek's sensitivity to landscape without abandoning abstraction.

Critics have long acknowledged the emotional power of Witek's monochrome surfaces. Critic Michael Brenson, writing in 1984 in The New York Times, championed Witek’s 80s paintings for their “play of darkness and light also has a theological dimension, which gives some of these works a feeling not unlike that communicated by Romanesque and early Christian art.” A 1988 Art in America essay observed that Witek's surfaces range from densely velvety to diaphanous and that they ultimately "refer to beauty" rather than simply being beautiful. In a 1993 Miami Herald review, Helen Kohen praised her Kendall Campus exhibition for presenting all‑black works that were "unique and superb", noting that although Richard Serra, Frank Stella and Ellsworth Kelly served as obvious models, Witek is "no copycat". Kohen emphasised how her use of the grid, unexpected oval forms and graphite powder created distinct patterns that give off a spiritual aura. The 2020 Hyperallergic review of Paintings from the 1980s noted that few artists unlock black's optical potential better than Witek; black shapes can vibrate when contrasted with neutral hues, and her compositions hum with subtle "buzzing." Such commentary underscores the sensory richness of her work despite its limited palette.

The art blog Two Coats of Paint compared Witek's lozenge paintings to those of Sean Scully's blocks and Ad Reinhardt's blacks, noting that these works challenge the viewer to examine subtle differences. This suggestion of "repetitive stress" encapsulates Witek's method: through repetition and restraint, she invites prolonged contemplation.

The Museum Wilhelm Morgner in Soest, Germany, which hosted a major exhibition of Witek's work in 2021, emphasised the tactile appeal of her materials. The gallery curator Juliane Rogge explained that, whether she works with wax crayon, oil, or acrylic on parchment, film, or canvas, Witek carefully calculates the specific properties of each medium. Viewers can almost feel the creased rice paper, velvety pastel, or buoyant watercolour, and the vitality of the works derives from a deliberate reduction of means and the interplay between geometric structures and handmade marks. Again, the titles, drawn from poetry or music, add further layers of meaning.

Joan Witek's career demonstrates how a seemingly simple constraint—a commitment to black—can open up vast expressive possibilities. Her works on rice paper and film, including those produced during her 1995 residency at Edward Albee's Montauk estate, reveal a sensitivity to materials and a profound understanding of how black interacts with light and surface. Whether creating monumental canvases, intimate drawings or ethereal watercolours, Witek demonstrates that black is not a synonym for absence but rather a living colour. A colour capable of evoking emotion, memory and time. Her contributions to modern and contemporary art lie in her relentless exploration of this single hue, which continues to inspire viewers and challenge preconceptions about abstraction.

An exhibition of Joan Witek's rice-paper pieces and selected works from the Albee Suite will be on view at Bartha_contemporary in an exhibition entitled "Black as a living colour" from October 23 to November 11